How Does Orton-Gillingham Treat Dyslexia

Written by Sandie Barrie Blackley, Speech-Language Pathologist

Published on August 1, 2022

If you have been exploring ways to help your child with dyslexia or other reading difficulties, you have probably heard the term “Orton-Gillingham.” So what is the Orton-Gillingham approach and how is it used in the treatment of dyslexia? Is it really the best approach? Is it up to date? We thought we’d provide a little background on Dr. Samuel T. Orton and Anna Gillingham and the development and evolution of their vital and highly successful approach to making struggling students into fluent and confident readers.

The History of the Orton-Gillingham Approach

During the 1920s and 1930s, Dr. Samuel T. Orton, a neurologist, described what he called strephosymbolia, or twisted symbols (Orton, 1925, 1937). Orton was puzzled by students who had great trouble reading despite having adequate intelligence. The study of brain-behavior relationships was still in its infancy, and the objective testing of intelligence (IQ) was also new. Modern brain imaging had not been invented.

Orton used the tools he had, including what he knew about brain function from his work with brain-damaged adults. He noticed that his struggling readers often had “static reversals and letter confusions.” But he found that the main problem was in “the process of synthesizing the word as a spoken unit from its component sounds” (Orton, 1937 cited in Hallahan & Mercer, 2001). Though nearly a century has passed since Dr. Orton made his observations, his findings are still central to our understanding of dyslexia: children with dyslexia do not automatically or intuitively recognize speech sounds and make the connection between the spoken word and the printed word.

To help such students overcome their reading struggles, Dr. Orton endorsed teaching phonics with multisensory inputs (visual, auditory, and kinesthetic).

Anna Gillingham, an educator with degrees from Swarthmore, Radcliffe, and Columbia Teachers College, had worked with “very high IQ children” (Swarthmore Bulletin, 2019). She met Dr. Orton in New York City in 1929 and over the next five years, she developed detailed methods for teaching reading using Orton’s ideas. In 1936, with her co-author, Bessie Stillman, she published what came to be known as the Orton-Gillingham manual: Remedial Work for Reading, Spelling, and Penmanship.

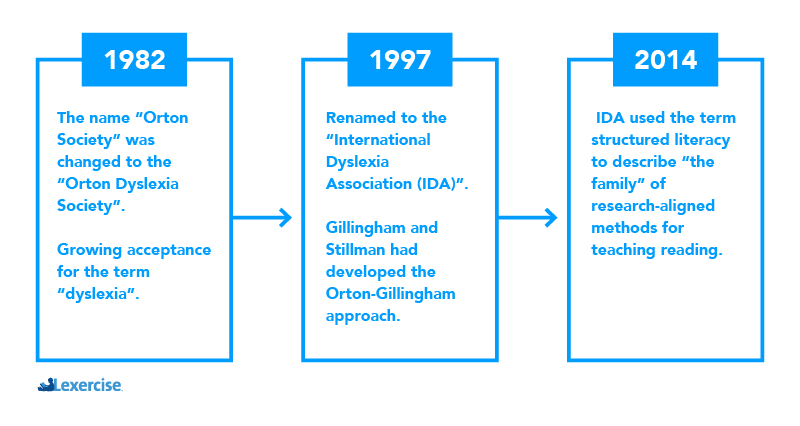

An Orton-Gillingham Dyslexia Approach Timeline

The history of the Orton-Gillingham approach is linked with the history of the professional association named for Dr. Orton: The Orton Society.

- 1982 – The original name, The Orton Society, was changed to the Orton Dyslexia Society to reflect the growing acceptance of the term “dyslexia” to describe the type of students Orton and Gillingham had worked with.

- 1997 – The Orton Dyslexia Society was re-named the International Dyslexia Association (IDA) to reflect a growing international consensus about how people learn to read. Leaders in the United States from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and the National Center for Learning Disabilities (NCLD) were part of this consensus.

- An important part of this growing consensus was a framework called The Simple View of Reading. The Simple View was first proposed in 1986 to clarify the role of efficient word recognition (decoding) in reading. It explains how “the ability to read age-appropriate material will be impaired if the child has difficulty understanding the language being read or recognizing the words of text, or both.” (Tunmer & Hoover, 2019) Students with strong skills in listening to material read to them but with weakness in recognizing the words of the text were more and more being called dyslexic. Orton had described this type of student as suffering from “twisted symbols.” Gillingham and Stillman had developed the Orton-Gillingham approach to help such students improve their weak word-reading skills.

- 2014 – The International Dyslexia Association (IDA) announced a major campaign to describe how reading should be taught, based on the research consensus. Some elements of what had been called the Orton-Gillingham method had research backing but others needed modernizing. IDA used the term structured literacy to describe the family of research-aligned methods for teaching reading. (See Malchow, 2014)

The Orton-Gillingham approach had become known as the gold standard for teaching reading to students with learning difficulties, including dyslexia. Private schools for students with learning disabilities specialized in it. Parents pressed their public schools to provide it as part of special education services. However, Orton-Gillingham methods had “seldom been well-defined, and clinical wisdom has been waiting for scientific research validation and explanation.” (Farrell & Sherman, 2011)

A Modernized Orton-Gillingham Approach

Structured literacy methods might be called the grandchildren of the Orton-Gillingham approach. The original Orton-Gillingham approach focused mostly on decoding. Modern structured literacy methods include procedures to help students with all aspects of reading, not just decoding. Structured literacy approaches share a set of features:

- Lessons and practice are adjusted to the student’s needs, with reference to the Simple View of Reading framework. Structured literacy methods are designed to build awareness of and conscious attention to the basic structures of language, which include:

-

- speech sounds

- letters

- letter-sound pronunciation and spelling patterns

- syllables

- words and word parts (e.g., prefixes and suffixes)

- phrases and sentences

- text passages

-

- Concepts are taught in clear, easy-to-understand terms, with examples, and modeling.

- Concepts are taught and practiced in a logical order, from simple to complex, in a cumulative manner.

- Teaching begins with the most basic skills the student has yet to master.

- Errors are used as learning opportunities, with prompt, targeted, and supportive feedback.

- Practice is designed to focus on specific concepts in a way that is not too difficult or too easy.

- Progress is checked in an ongoing manner to adjust instruction and practice.

Other aspects of instruction are how often lessons are taught and how much practice is done. We know that students with reading difficulties need more practice than do their peers. But getting students to do enough practice can be hard! This is especially true when students are taught in groups, as they are in schools. How much and how often is typically defined in terms of lessons per week and length of lessons. But lessons often don’t include much, if any, practice. For example, Nicholson (2011) reported this observation by Phillip Gough, one of the authors of the Simple View of Reading framework:

“Our children do not read enough. A few years ago, I observed a first-grade classroom in Austin and watched a reading lesson. The lesson lasted half an hour and I timed with a stopwatch the minutes the children spent actually reading, that is, looking at print and deciphering it. It was less than five.” (p. 11)

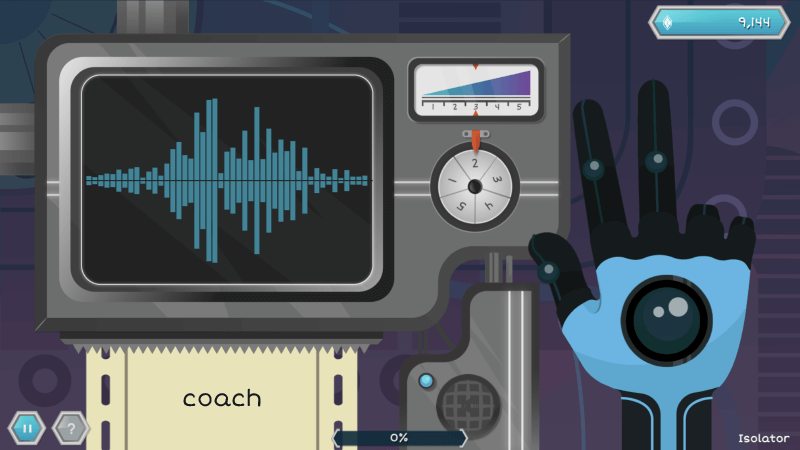

In the coming years, Gough’s stopwatch would be replaced with high-tech ways for tracking how much and how often students are “looking at print and deciphering it.”

In the more than eight decades since the Orton-Gillingham approach was first described it has been continually informed through the science of reading. It is steadily being improved with new technologies. The modernized Orton-Gillingham approach referred to as structured literacy is leading the way to more and more effective intervention systems for dyslexia and other types of literacy difficulties.

The Lexercise Structured Literacy CurriculumTM

The Lexercise Structured Literacy CurriculumTM combines a science-backed curriculum with the latest in educational technology, modernizing the

Orton-Gil lingham approach to maximize effectiveness. We combine face-to-face, individually paced lessons

lingham approach to maximize effectiveness. We combine face-to-face, individually paced lessons

with online games for daily practice, plus parent-teacher support materials for offline activities.

If you are looking to help your child manage dyslexia and to become a fluent, confident reader, check out our online dyslexia therapy solutions or contact us for more information.

References

Farrell, M. L. and Sherman, G.F. (2011). Multisensory Structured Language Education. In J. R. Birsh (Ed.), Multisensory Teaching of Basic Language Skills (3rd ed., pp. 25-47). Brookes.

Hallahan, D. and Mercer, C.D. (2001). Learning Disabilities: Historical Perspectives. Office of Special Education Programs (Learning Disabilities Summit). Archived from the original on 2007-05-27. Retrieved 7/14/22 from http://www.nrcld.org/resources/ldsummit/hallahan2.shtml

History of IDA. Retrieved 7/14/22 from https://dyslexiaida.org/history-of-the-ida/

How a Class of 1900 alumna influenced dyslexia research. (2019). Swarthmore Bulletin. Retrieved 7/14/22 from https://www.swarthmore.edu/bulletin/archive/fall-2019-issue-i-volume-cxvii/second-looks.html

Malchow, H. (2014). Structured Literacy: Teaching Our Children to Read, Lexercise Guest Blog Post. Retrieved 7/14/22 from https://www.lexercise.com/blog/structured-literacy

Nicholson, T. (2011). The Orton-Gillingham approach: What is it? Is it research-based? Learning Difficulties Australia Bulletin, 43 (1), 9-12.

Orton, S. T. (1937). Reading, writing, and speech problems in children. New York: W. W. Norton.

Orton, S. T. (1925). “Word-blindness” in school children. Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry, 14, 581-615.

Spear-Swerling, L. (2022). An Introduction to Structured Literacy and Poor-Reader Profiles. In L. Spear-Swerling (Ed.) Structured Literacy Interventions: Teaching Students with Reading Difficulties, Grades K-6 (p. 4). Guilford.

Tunmer, W.E. & Hoover, W.A. (2019). The cognitive foundations of learning to read: a framework for preventing and remediating reading difficulties, Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 24:1, 75-93, DOI: 10.1080/19404158.2019.1614081

Improve Your Child’s Reading

Learn more about Lexercise today.

Schedule a FREE

15-minute consultation