Foundational Concepts: Where Literacy Begins

Written by Sandie Barrie Blackley, Speech-Language Pathologist

Published on January 25, 2022

The Importance of Early Literacy

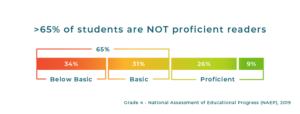

As we begin the new year (and, by the way, Happy New Year!) we’d like to do all we can to empower effective and efficient reading instruction. The science of how to teach reading effectively and efficiently has never been clearer. We know the main building blocks for proficient literacy and how to teach them. And yet, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), often referred to as the “nation’s report card,” the percentage of U.S. public school students reading at proficient levels has dropped over the last two years (NAEP, 2019). Mississippi was the only state in the country where 4th grade reading scores improved. As Mississippi demonstrates, when parents, teachers, administrators, and policy makers work together to apply reading science, reading outcomes improve!

The more we understand about the building blocks for language and literacy, the better equipped we are to support our children and students as they learn these essentials and improve their reading and writing. So, over the next few months, we’ll be examining the most basic and essential elements of language and literacy.

Let’s start with how children learn words. How does a child learn the meaning of a word like frog?

How does she learn to pronounce the word frog? In fact, this all begins inside the “black box” of a baby’s brain, long before the child can walk or even sit up!

Somehow, we learn to speak. But by the time we’re old enough to wonder how we went about it, we can no longer remember our own experience of language learning. It seems to have “just happened.” Even now, when we learn a new word we don’t think much about it. Word learning is largely an unconscious process. For example, do you remember exactly when and how you learned the word coronavirus?

Somehow, we learn to speak. But by the time we’re old enough to wonder how we went about it, we can no longer remember our own experience of language learning. It seems to have “just happened.” Even now, when we learn a new word we don’t think much about it. Word learning is largely an unconscious process. For example, do you remember exactly when and how you learned the word coronavirus?

As infants, we are surrounded by sensory stimulation. We hear the sounds that people make and watch their faces, gestures, actions, and reactions. Nobody stops to explain to us the formal meaning of words, but gradually we begin to make associations between words and actions—to comprehend the language even if we do not precisely understand the meaning (or spelling) of the words. We refer to all of that incoming stimulation, including visual, auditory, touch, etc., as input.

The linguist Stephen Krashen studied this process, especially in relation to learning to understand and speak a second language. Krashen’s theory, called comprehensible input, describes how adults learn to understand and speak a second language. This theory, now supported by scientific research, is easily illustrated by watching and listening to a story being told in a language you do not yet speak.

As an example (for those who do not speak Spanish), in the Fabulaudit series on YouTube, native Spanish speaker Francisco tells simple stories entirely in Spanish. We listen as we watch his face, his mouth, his expressions and gestures, and the drawings and words he scribbles on the whiteboard. He rarely translates or explains in English and there’s no “repeat after me” memorization. We watch and listen, and, somewhat like a child, absorb the story.

This sensory input feeds complex networks of mental representations that underpin spoken and, later, written language. In future posts, we will examine some of the elements of language learning, how the remarkable human brain connects spoken language to written symbols for reading and writing and, finally, how the Lexercise Structured Literacy Curriculum™ helps students build proficient reading, spelling and writing using these building blocks.

Learn more here about how Lexercise Therapy can help struggling readers.

Improve Your Child’s Reading

Learn more about Lexercise today.

Schedule a FREE

15-minute consultation