FAQ Friday: Can struggling readers benefit from technology?

Written by Sandie Barrie Blackley, Speech-Language Pathologist

Published on September 28, 2012

Can struggling readers benefit from technology? The answer is a resounding YES! However, from there, we are left with many further questions: What is assistive technology? Which technology works the best for struggling readers, writers, and spellers? At what point do we introduce technology to help a child overcome reading deficits? How do we balance technology with “regular” instruction?

Connecting Technology with A Struggling Reader

In today’s post, which is co-written with assistive technology consultant Beth Sinteff, we’ll focus on the third and fourth questions — the “when” and “how” of assistive technology. For more information on the first two questions, see our earlier posts here and here, and watch these Live Broadcasts by Mary K. Alexander and Miki Feldman-Simon.

When and How to Use Assistive Technology

Sandie: With regard to the third and fourth questions, I don’t think there is a single or simple answer. There is very little current research to support a specific approach to the use of assistive technology, such as keyboarding, in therapy for dyslexia, dysgraphia, or other language-processing disorders. In practice, it is a matter of carefully assessing the child’s needs and support infrastructure, where the blocks are, and what can be done to deal with them, and then exercising clinical judgment.

Beth: I have not found a good guideline that says specifically when to introduce these tools. I generally let families know that I believe that technology should be introduced very early to support learning — much earlier than we currently do for students who are working grade levels below their age. I do not introduce these tools to overcome reading or writing problems but as a support for making reading or writing more enjoyable and, hopefully, easier.

Sandie: Here’s an example of what I mean by clinical judgment. You may remember Emerson, our homeschooled 9-year-old “word wizard.” Emerson has just restarted treatment. While his spelling has improved, he has a lot of transcription issues with handwriting (dysgraphia) and also really needs some structure for proofreading. So I decided that Emerson needed to type his academic writing projects. That way, the editing would not be so laborious and he could access Ginger Software for spelling and grammar checking. (Typing and Ginger Software are just two of many assistive technologies.)

But Emerson is only 9 and keyboarding is not generally taught to 9-year-olds. So, in deciding whether this was an appropriate approach, I considered that Emerson is very bright, has an incredible “need for speed” and has a foundation of six months of structured literacy treatment. It seemed to me that assistive technology could make a huge difference in his academic performance.

I want to emphasize that we are not discounting the importance of handwriting. We are continuing to work on very specific and directed handwriting practice with Emerson. We’ll talk more about handwriting in another post.

Beth: I believe firmly that keyboarding could be taught to younger children. Some schools now have keyboarding classes in Kindergarten. If a child knows about letters and sounds and that these combine to make words, there is no reason that child cannot begin to learn keyboarding skills. I have successfully introduced keyboarding to children as young as 3 1/2 years of age who could not yet speak but knew about letters and sounds.

Sandie: I’d have to add that Emerson is not typical in any way. He is very bright and has a very organized and attentive mom.

Beth: Oh yes, parent support is imperative. I work with a number of parents who know it may be a bit harder to use technology initially but are able to see the future in its use and the reduced dependence on others (parents, aides, etc.). Those parents are generally very organized or they take instruction very well from the therapist. I’ve even worked with some parents who soar and get way ahead of me (yeah!) and have helped their children achieve even more.

I consider the technology an independent tool. If a parent or other adult is doing the writing, reading, or typing for a child, then it takes away the child’s ability to do this independently. If independence is something the parent wants to nurture, then introducing technology earlier is better.

Sandie: Beth makes a good point about taking the long view. We may think that because children are so adept at technology they “get it” or “know it” from birth. In fact, just like reading itself, technology has to be taught to the child in an organized, systematic way.

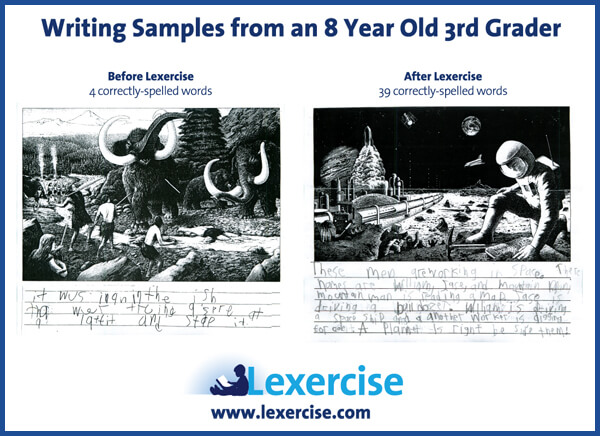

When we evaluate an individual’s progress, we use a statistic called Correct Writing Sequences (CWS), which is a way of monitoring writing progress that goes beyond spelling and also includes grammar and writing conventions such as punctuation and capitalization. In his handwritten examples (shown above), Emerson went from 0 CWS to 33 CWS after 20 online Orton-Gillingham treatment sessions. In his typed exercises, Emerson has advanced from 54 CWS in December 2011 to 142 CWS in September 2012. (The 4th-grade expectation is 27-38 CWS, so he has more than quadrupled that!) Emerson’s mom, Julie Barney, reports that his typed draft of one week’s writing assignment took about the same length of time Emerson had spent on each of his handwriting samples. You can see that his progress is very significant, but it doesn’t happen overnight — or without a lot of focused practice and parental support!

Beth: That’s right. The use of any technology requires good instruction (reading or writing), training on the technology to support the process (literally the key presses needed), and training on how to use the technology to be a better reader or writer. The technology itself does not teach reading or writing. It requires all of the above to be useful. When I introduce technology, I am not shifting emphasis away from instruction. I use the technology to support learning to read and write and incorporate specific instructional goals to go with the technical skills I am teaching. If we can use technology to support the academic achievement of a child who is bright enough but is working two grade levels below his or her age — and if we have the support from parents and teachers — there is an opportunity to make a great change in that child’s life.

Sandie: Absolutely. The clinician has to decide for each individual, given the child’s life circumstances, school situation, and language processing skills: what role might assistive technology play, and how and when.

Beth: This is an individual decision. But if you have a plan for how to introduce technology that is systematic and you know the features of specific technologies, assistive technology can make great changes in the lives of students. Plus, very importantly, many students want to use technology. Students who use technology are often more accepted by their peers because they can keep up better. And, teachers will often raise their expectations of students once they see technical abilities increase and support learning.

Sandie: Thank you, Beth! And thanks again to Emerson and his mom, Julie!

If your child has symptoms of dyslexia, such as difficulty reading, writing, or spelling, Lexercise can help. Take a look at our Online Dyslexia Testing and Treatment page or contact me directly at Info@Lexercise.com or 1-919-747-4557.

—–

Beth Sinteff is an assistive technology (AT) consultant for Lexercise. She is a certified speech-language pathologist (CCC-SLP) and holds an M.S. from the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. Beth provides speech-language therapy services in a school for students with autism and social-emotional challenges as well as to private clients through her consultancy.

Improve Your Child’s Reading

Learn more about Lexercise today.

Schedule a FREE

15-minute consultation