Why Letter Formation Matters for Reading and Writing

Written by Sandie Barrie Blackley, Speech-Language Pathologist

Published on October 16, 2025

Parents and teachers spend a lot of time teaching young children about letter names and letter sounds, but, unfortunately, if letter writing is taught at all, it is often an incidental aspect. In the USA, the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) provide no specific guidance on when or how to teach letter writing, and professional development programs for teachers rarely include research-backed guidance or materials for teaching letter writing. Some structured literacy programs include instruction in letter writing, while others don’t.

The current science of reading supports a phonics approach that integrates letter writing, decoding, and spelling. For example, when learning about the letter -b-, students should learn to do all of the following in an interconnected, back-and-forth manner:

- Identify it (“Point to the -b-.”)

- Name it (“What is the name of this letter?”)

- Pronounce its common speech sound (“What sound does -b- spell?”)

- Form it using a pencil or marker on paper or a whiteboard (“Write a -b-.”)

While there are a number of commercially available handwriting programs that include instruction on forming letters, these programs typically do not include integration with phonics and spelling.

What is Letter Formation?

Letter formation refers to the explicit motor plan for handwriting each letter. For lowercase letters, this includes:

- The entry stroke: where and how to begin

- The movement pathway: from beginning to end

- The exit stroke: where and how to end

What Research Says About Teaching Letter Formation

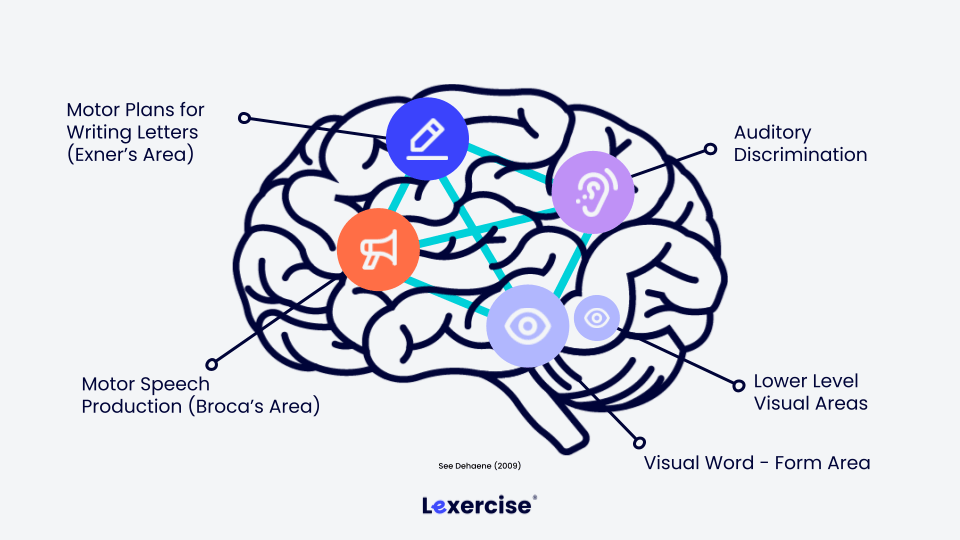

Research has shown that students who are taught letter formation along with letter names and sounds not only develop better handwriting but also exhibit stronger reading, spelling, and writing skills. This is true even for older, struggling readers and writers. Neuroscience reveals that the brain areas that support phonics and word recognition are interconnected with those that support letter writing, as shown in the infographic below.

The letter-sound pathways in the brain are strengthened when a letter’s name and speech sound(s) are connected with the motor plans for correct letter formation. Research supports the following teaching practices:

- Letter formation should be taught along with letter-sound association (phonics), decoding, and spelling.

- Lowercase and uppercase letters should be differentiated, but lowercase letters should be prioritized because most letters in text are lowercase.

- There should be explicit instructions on how to write each lowercase letter. (There is a correct way to write each letter.)

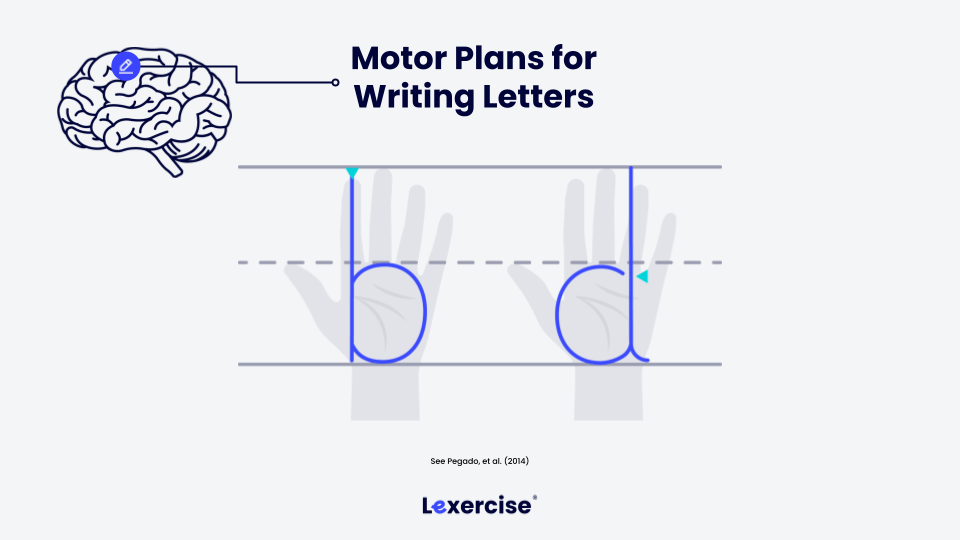

- Each letter should be taught as a (mostly) continuous movement pathway rather than as a static shape (e.g., balls and sticks) because static shapes are easily inverted or reversed in visual memory and do not facilitate fluent, automatic writing.

- There should be guided practice using visual cues and immediate feedback.

- There is little evidence to suggest that one specific handwriting style is better than another. The key is for letters to be written legibly, automatically, and fluently. See: Study says there may be a better cursive style for students (Education News Today, January 24, 2024).

Mental Guidance for Letter Formation

Precise and automatic letter formation facilitates letter and word recognition, spelling, written language, and even note-taking. Students who are taught to form letters by hand using a structured, movement-based approach recognize letters more quickly, generate ideas in writing more easily, and have better reading comprehension. Explicit instruction with visual motor guidance helps establish a distinct movement path for each letter. For example, the lowercase letters -b- and -d- can appear to be similar but reversed images. However, the movement pathway for writing these two letters is dramatically different.

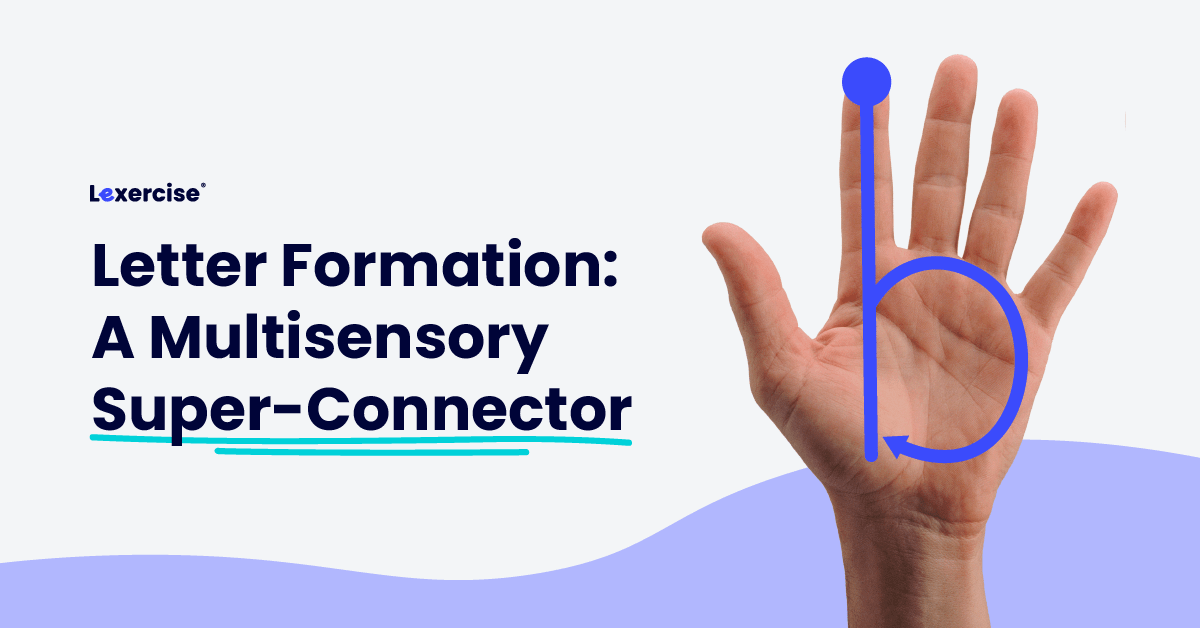

The palm of the hand is an excellent, multisensory guide for learning the movement pathways for lowercase letters. Using the palm of the hand as a mental guide:

- The entry stroke for a lowercase -b- is a downstroke from the tip of the pointer finger.

- The entry stroke for a lowercase -d- is a backstroke across the top of the palm beginning where the ring finger connects.

The mental guidance for right-handed and left-handed writers is similar. The main differences are related to the entry and exit strokes. For example, when forming a lowercase -b-, a right-handed student would use the left palm as mental guidance, with a downward entry stroke from the pointer finger. A left-handed student would use the right palm for mental guidance, with a downward entry stroke from the ring finger.

Right-Handed Guide

Left-Handed Guide

Integrating Decoding, Spelling, and Letter Formation in the Classroom

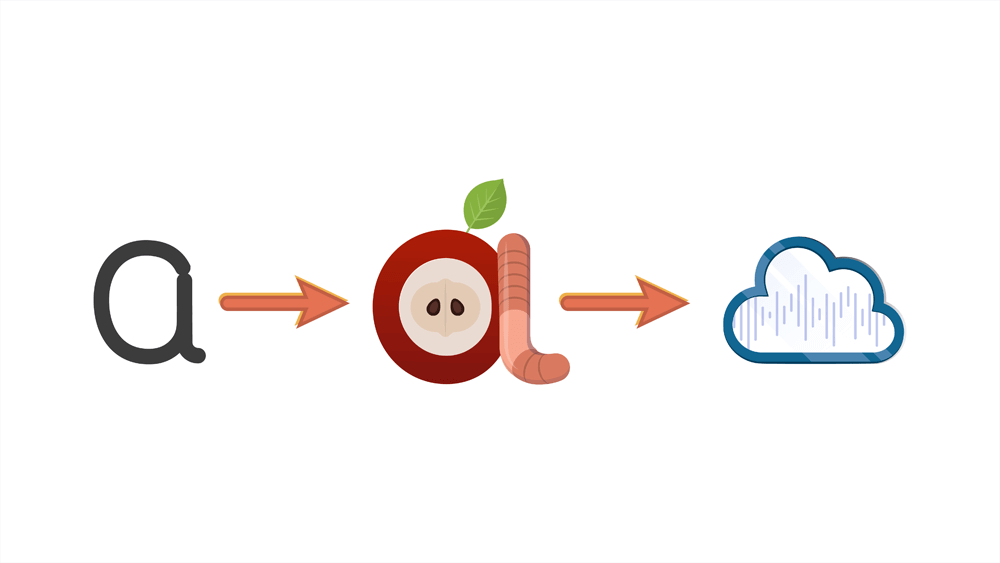

Research-backed phonics methods integrate decoding, spelling, and letter formation. The letter name and its most common speech sound are introduced together, often using a keyword that begins with the letter-sound. For example: -a- → apple → “æ”.

In the same lesson, the motor pathway for forming a lowercase -a- is taught. It helps to use a visual mental guide that makes the entry stroke, movement pathway, and exit stroke explicit.

Practice is essential for both letter-sound associations and letter formation. Online practice is helpful as it can provide an adequate number of practice responses with immediate feedback and motivational support. See, for example, the Lexercise Online Games. Of course, students also need practice writing words on physical surfaces, like whiteboards or paper. When spelling words in classroom activities, they should use the letter formation pathways they have learned.

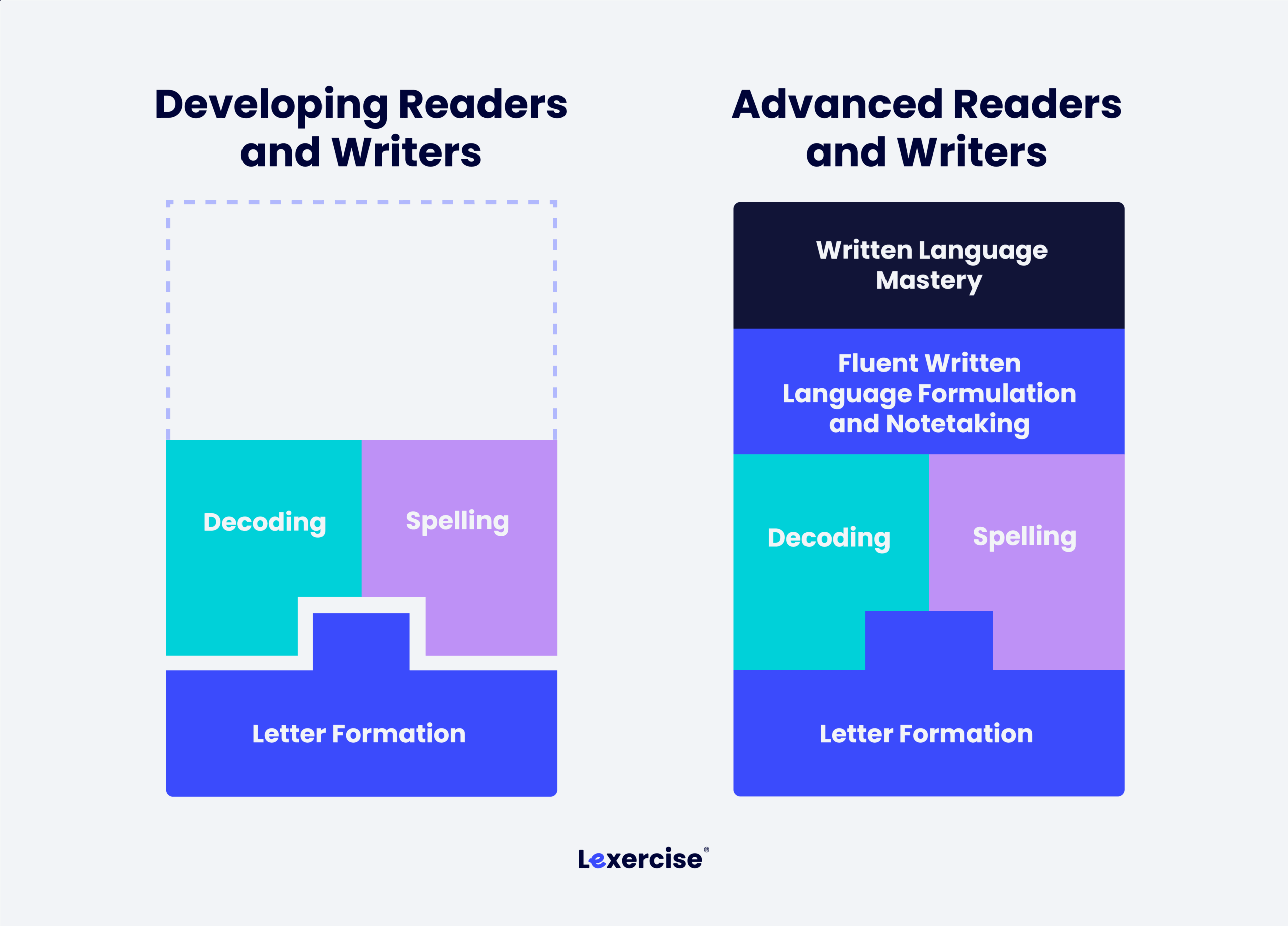

The science of reading demonstrates that developing readers and writers benefit from the integration of letter formation with decoding and spelling. But even as students advance to upper-level literacy skills, these early skills continue to serve them because students with automatic and fluent handwriting are better able to formulate written language. They are better able to use handwriting for note-taking, which has been shown to be faster and more efficient than note-taking using digital devices, and certainly teaches the notetaker more than an AI notetaking app. Letter formation is a literacy super-connector.

Lexercise: Literacy Resources for Teachers and Parents

Whether you’re a parent or teacher, Lexercise offers practical, research-backed tools to connect handwriting with reading and spelling. Explore our other literacy resources to support students with Dyslexia, Dysgraphia, and other reading and writing challenges.

Improve Your Child’s Reading

Learn more about Lexercise today.

Schedule a FREE

15-minute consultation