DLD and Dyslexia: Navigating Dual Challenges in Learning

Written by Sandie Barrie Blackley, Speech-Language Pathologist

Published on November 11, 2025

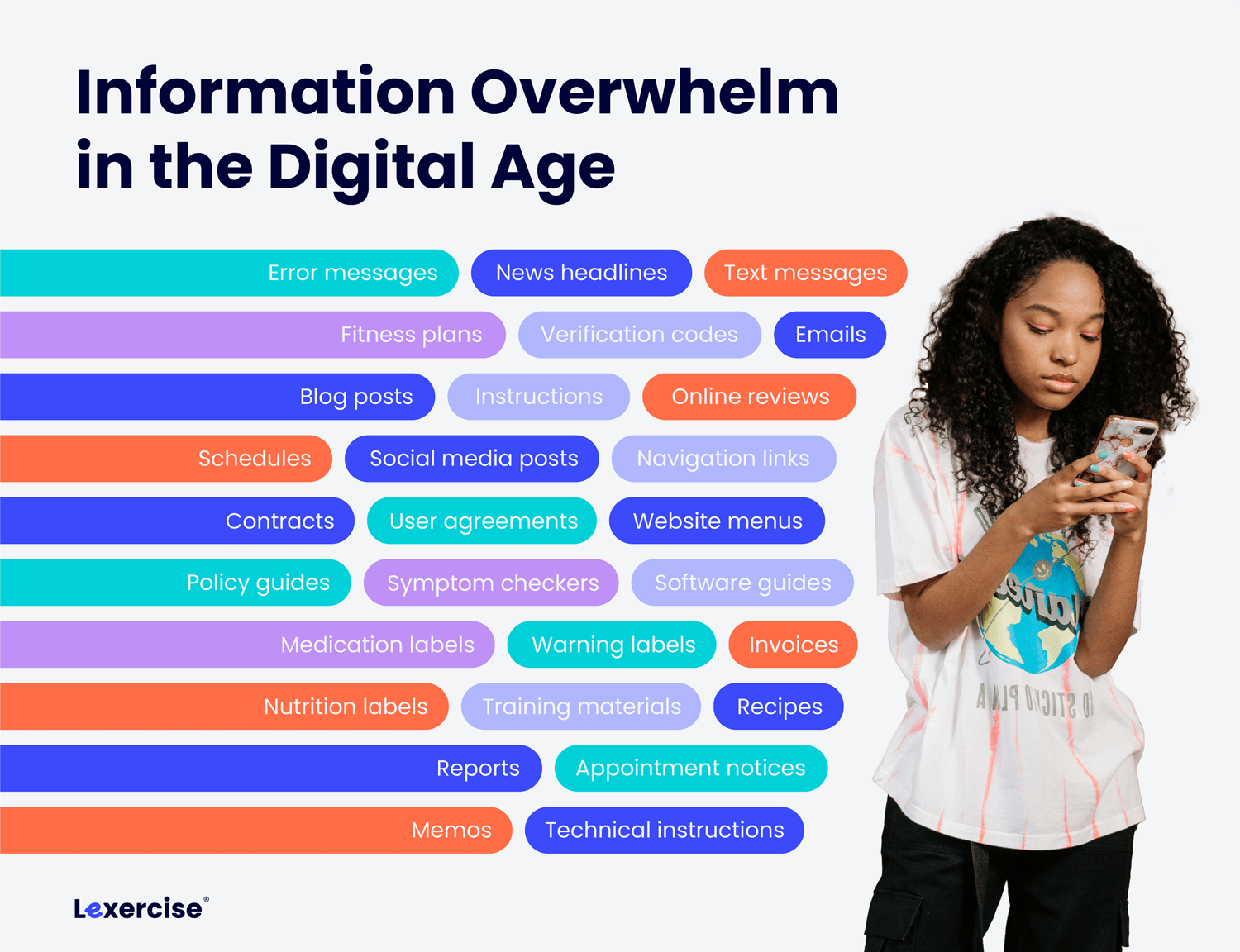

Modern life is constantly bombarding us with information. Our ability to process this barrage of information impacts not only education and job success but even our safety, health, and overall well-being.

Today’s communication challenges are especially daunting for someone with a language processing disorder, like developmental dyslexia or developmental language disorder (DLD) – and it is doubly so for those struggling with both dyslexia and DLD. Fortunately, targeted interventions initiated early and used correctly can help overcome language processing challenges.

What is Developmental Language Disorder?

Developmental Language Disorder (DLD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder that affects a person’s ability to understand and use spoken language effectively. DLD is a common disorder, affecting approximately 7.5% of the population (about two children in every classroom). DLD is often misunderstood and undiagnosed.

What Causes Developmental Language Disorder?

DLD is often influenced by genetic factors and frequently runs in families. The underlying cause is complex and not fully understood, but it is not caused by a lack of intelligence, poor parenting, hearing loss, or learning multiple languages.

What is the Difference Between DLD and Dyslexia?

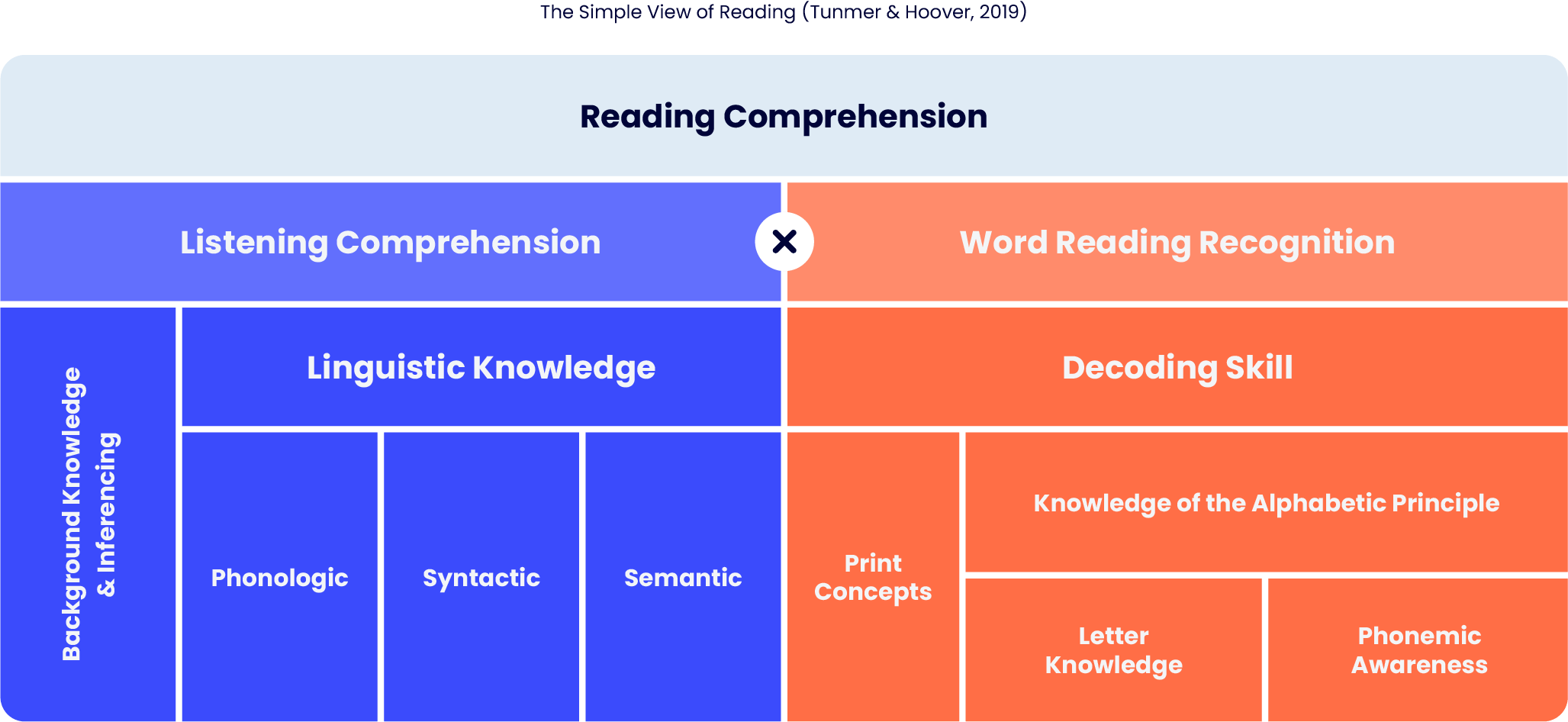

The Simple View of Reading helps us understand the impact of DLD and dyslexia on reading proficiency. Simple View explains that a student’s reading comprehension is their listening comprehension multiplied by their ability to recognize written words.

DLD primarily affects listening comprehension, while dyslexia primarily impacts decoding and the identification of written words.

- Individuals with DLD alone may struggle to understand and formulate sentences and ideas using spoken language, but have relatively stronger decoding skills. The interventions that help people overcome DLD focus on the individual’s specific language deficits (e.g., phonologic, syntactic, and semantic), targeting vocabulary and sentence structure in meaningful contexts such as story-based activities.

- People with dyslexia alone typically experience the opposite phenomenon – relatively more difficulty with decoding and word recognition, with a relative strength in understanding spoken language. Effective interventions for dyslexia are specifically focused on speech sounds and how they are represented by letters, as well as spelling patterns that represent meaning, including prefixes and suffixes.

DLD and Dyslexia Comorbidity: Navigating Dual Challenges in Learning

When a student struggles with reading comprehension, effective intervention depends on a clear understanding of their specific language processing strengths and weaknesses.

While both DLD and dyslexia involve underlying language weaknesses, DLD centers more on broader oral language functions (syntax, semantics), whereas dyslexia centers more on decoding and word-level reading.

But human language functions are highly interconnected, and people can and often do have elements of both DLD and dyslexia. In some samples, nearly 48% of children with DLD also meet the criteria for dyslexia.

In the Classroom: Where Struggles Tend to Show

Imagine a student who scores below basic proficiency on end-of-grade reading tests and struggles to complete school reading and writing assignments. In the classroom, teachers may observe a pattern of symptoms that can help them better understand the basis of a student’s reading difficulties.

| Symptom Domain | Characteristics – DLD only | Characteristics – Dyslexia only |

|---|---|---|

| Language comprehension | Comprehension is impaired both when listening and when reading. This is the hallmark of DLD. | Comprehension is much better when listening than when reading. |

| Word recognition | Approximately half of children with DLD have a relative strength in decoding compared to their ability to understand what they read. In its extreme form, this is known as hyperlexia. | Understanding word meanings is a relative strength, but identifying the written word (decoding) is the major stumbling block. This is the hallmark of dyslexia. |

| Oral reading fluency | Sentence structure context does not help, so reading is similar for passages and isolated word lists. | Sentence structure context helps, so reading is better for passages than for isolated word lists. |

| Writing | Spelling may be impacted, but so are vocabulary, grammar, and sentence structure. | Spelling errors predominate. Vocabulary and sentence structure are relative strengths. |

| Reasoning strengths | Strength is often seen in nonverbal reasoning, such as map navigation, interpreting expressions and gestures, and following graphic (wordless) instructions. | Strength is often seen in connecting concepts and complex patterns through stories and personal experiences, rather than rote memorization. |

| Anxiety triggers | Anxiety is often triggered by pressures for oral communication in social and instructional contexts. | Anxiety is often triggered by demands for reading aloud and timed reading and/or writing tasks. |

Why Traditional Accommodations May Fall Short

Struggling readers often have a combination of DLD and dyslexia. Effective intervention requires the use of tools that are targeted to the individual’s strengths and weaknesses.

A student with DLD, who has a relative strength in decoding but weaknesses in listening comprehension and sentence formulation, will not benefit significantly from an intervention that focuses only on decoding. Likewise, a student with dyslexia, with a relative strength in listening comprehension and oral language, won’t benefit much from an intervention that focuses mostly on vocabulary and syntax.

A structured literacy curriculum that includes the following domains can be adjusted for individual students:

- Phonemic awareness and phonics

- Orthography

- Morphology

- Semantics

- Syntax

- Discourse comprehension

- Writing and written expression

What Actually Works: Proven Strategies for Success

The science of reading has identified actions that help students overcome language processing difficulties like DLD and dyslexia.

- Early Intervention: Initiating intervention in early childhood for children with DLD and/or dyslexia risk factors leverages the brain’s plasticity, facilitating more robust language development and stronger early literacy skills.

- Multimodal Approach: The most effective interventions involve close collaboration between parents and professionals to ensure language goals are supported across all environments (home, school, and social settings).

- Parent-Implemented Intervention: Parent-guided interventions are highly impactful. Training parents to use specific techniques and instructional routines has been proven highly effective for both children with DLD and dyslexia.

- Duration and Intensity: Evidence suggests that interventions over a longer duration (e.g., 8 weeks or more) are generally associated with better outcomes than short, high-frequency periods of therapy. Intensity, best measured in the number of response opportunities provided to a student per day, is highly predictive of progress.

- Targeted vs. General: Interventions with highly specific, clear, logically sequenced, language-based objectives are more effective than general experience-based language activities. For example, following a science lesson about the forms of water, a teacher might have students complete two separate worksheets that focus on targeted content in different ways.

- Worksheet 1 (Meaning-based) – Write a true and grammatical sentence using each of these terms: liquid, solid, gas, ice, vapor, fluid.

- Worksheet 2 (Word structured based) – Spell the missing letter(s) in each of these terms:

- li_uid

- sol_d

- g_s

- i_e

- vap_

- flu_d

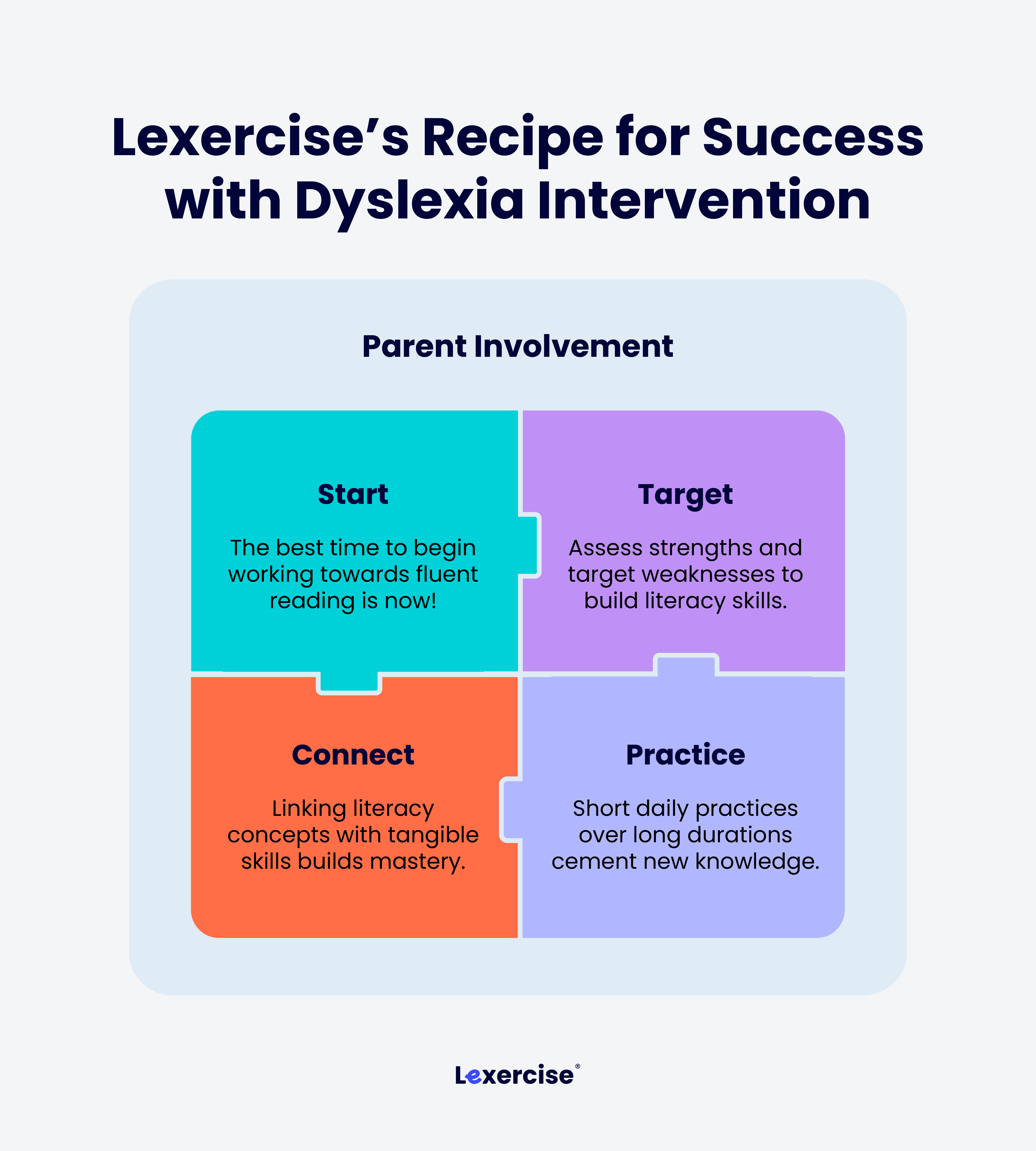

Lexercise: Helping Kids with Dyslexia and DLD Succeed

Lexercise provides personalized, evidence-based, effective intervention for students, no matter where they live. Free, online screening (here’s our DLD test) and targeted assessment tools help identify each student’s strengths and weaknesses. Students can start receiving help right away, without the delays and high costs associated with extensive diagnostic evaluations.

A qualified Lexercise structured literacy (Orton-Gillingham) therapist partners with the parent(s) to customize intervention, using online lessons, shared activities, and motivating, game-based practice, all on a schedule that works for the family. Students who use Lexercise make at least a year’s worth of reading growth in the first eight weeks.

Request a free consultation with one of our teletherapy partners today.

Improve Your Child’s Reading

Learn more about Lexercise today.

Schedule a FREE

15-minute consultation